History

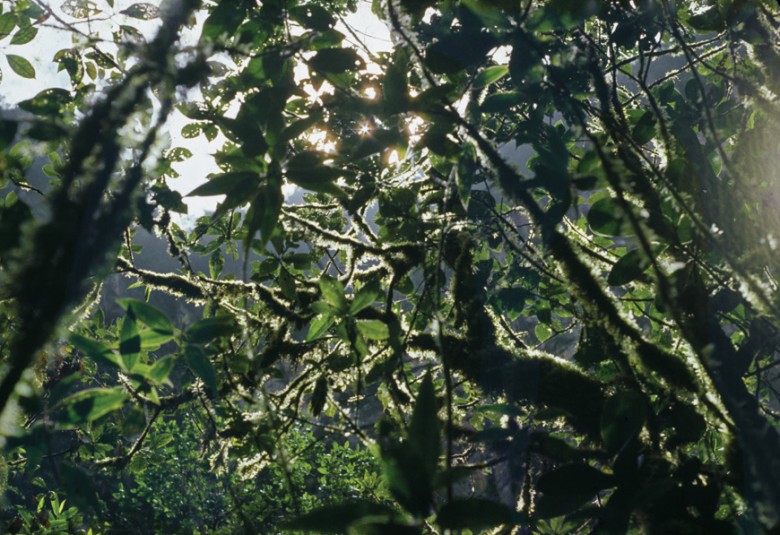

The Puinave are a minority ethnic group of Colombian origins. Although little is known about how and when they arrived in Venezuela from the Inirida region of Colombia, they now live in settlements in the vicinity of Guasuripana and San Fernando de Atabapo.

This Puinave handbag illustrates the group's artisanal skill. The craftsperson added a many small details that contribute to the whole object.

Although some scholars believe their language is independent, others think that it is part of a subgroup of various languages, including the Tucano and the Macú.

In the past, the Puinave moved often, living in villages for short periods of time. Contact with the criollo population, however, has altered this nomadic way of life, and they now tend to live in permanent houses. Each village and its surrounding territory are owned collectively by the inhabitants.

Ritual and Tradition

The Puinave have a rich ritual and religious life. The celebration of the Yurupary ceremony, for example, is an important rite that restores equilibrium to all beings and to re-establish ancestral connections. It is a rite of passage marking the occasion when a young man leaves the realm of women and children and takes on his adult responsibities.

Another example of the eye-catching jewelry made from the by-products of food preparation. The necklace's creator ordered the pieces by size, producing a harmonious effect.

During the Yurupary cermony, youth are initiated into the ways of the sacred flute, and are lashed with whips to strengthen their willpower. Elaborate food preparations are made for the ritual, including yaraque, a beverage made with cassava and water, and pai, made with fermented cassava and ñame.

Sustenance

Subsistence activities like hunting and fishing are collective efforts and the surpluses are traditionally shared among the group. However, an increasing dependence on a non-traditional criollo economy has altered this basic sense of reciprocity and solidarity among the Puinave.

Subsistence activities like hunting and fishing are collective efforts and the surpluses are traditionally shared among the group. However, an increasing dependence on a non-traditional criollo economy has altered this basic sense of reciprocity and solidarity among the Puinave.

Nasas, used for fishing in shallow, calm waters, are constructed from mamure fiber (Heteropsis spruceana) or tirite (Ischosiphon aruma). Some are conical, with a handle. Others have a trumpet-like shape, with a narrow middle. During this kind of fishing, Barbasco (Tephorsia toxicaria) is placed in the water to stun the fish, facilitating its capture.

The Puinave fish all year. During the dry season, when water levels are low, they use bait, harpoons, and bows and arrows. During the rainy season, when they must be more efficient, they use ingeniously devised woven fishing traps, called nasas, as well as woven cacures. Fishing with barbasco and other toxic plants is a festive activity in which the women and children participate.

This small Puinave blowpipe is made for children. More than a toy, it is a real weapon to train young hunters.

They trap limpets and picures on the riverside, and hunt with blowguns equipped with sighting beads made from animal teeth. The blowguns shoot darts that are covered in curare, a poison. The Puinave also hunt with rifles, which makes them dependent on ammunition supplied to them by criollos.

These small petate baskets are a beautiful example of the basketmaking in the Negro River region, where the use of chiquichique for crafts is popular.

In a trade system of "advances", the Puinave receive goods on credit from criollos. These goods, which have come to be seen as necessities, include boat motors, gasoline, radios, sewing machines, and canned foods. The criollos profit twice: from inexpensive labor and from the sale of indigenous goods such as fibers, rubber, pendare, hides, and feathers. This system has collapsed the traditional indigenous economy.

Fabrication

The Puinave who live in the Apure, Bolivar, and Amazonas regions of Venezuela have become acculturated with the criollo population, and share their language and style of dress. All men wear shirts and pants, and the women wear cotton dresses.

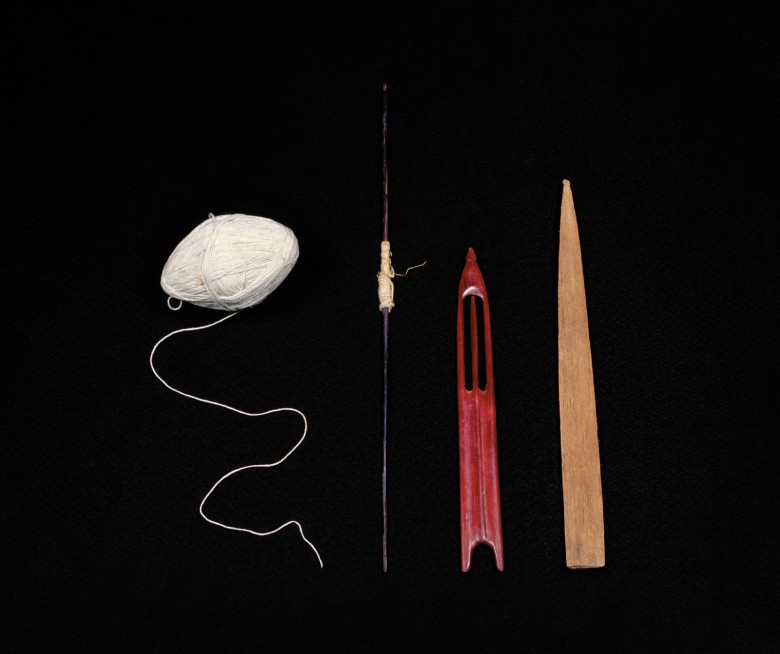

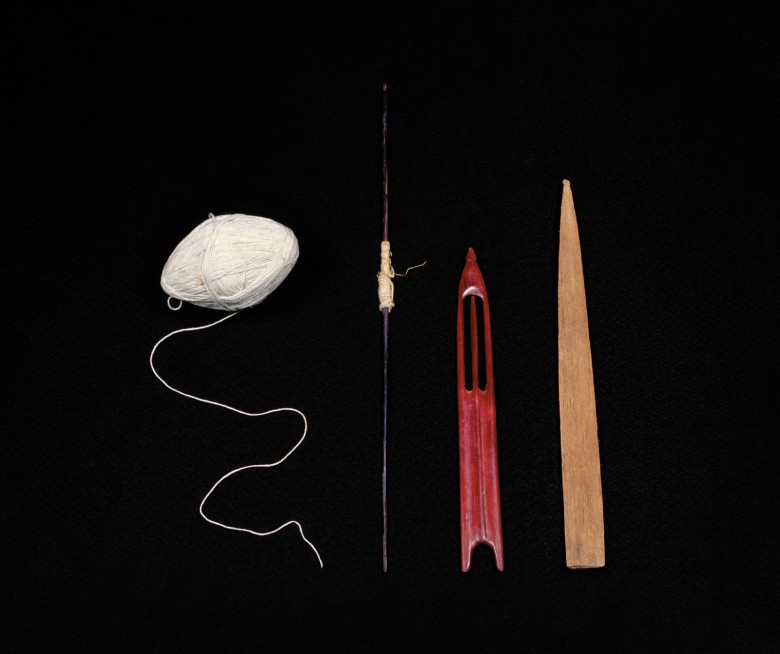

This delicate needle, made from polished Brazilwood, stands out as an extremely sophisticated tool.

Many of their domestic goods also are of criollo origin. The hammock is perhaps the most important traditional domestic artifact. It is woven of moriche or cumare fibers on rustic looms that also are used to make child carriers.