History

Although variously called Makiritare, De’cuana, Mainongkong and Mayongong, members of this group describe themselves as "Ye’kuana," which means "people of the curiara." Their name is made up of the words ye: wood; cu: water; and ana: people.

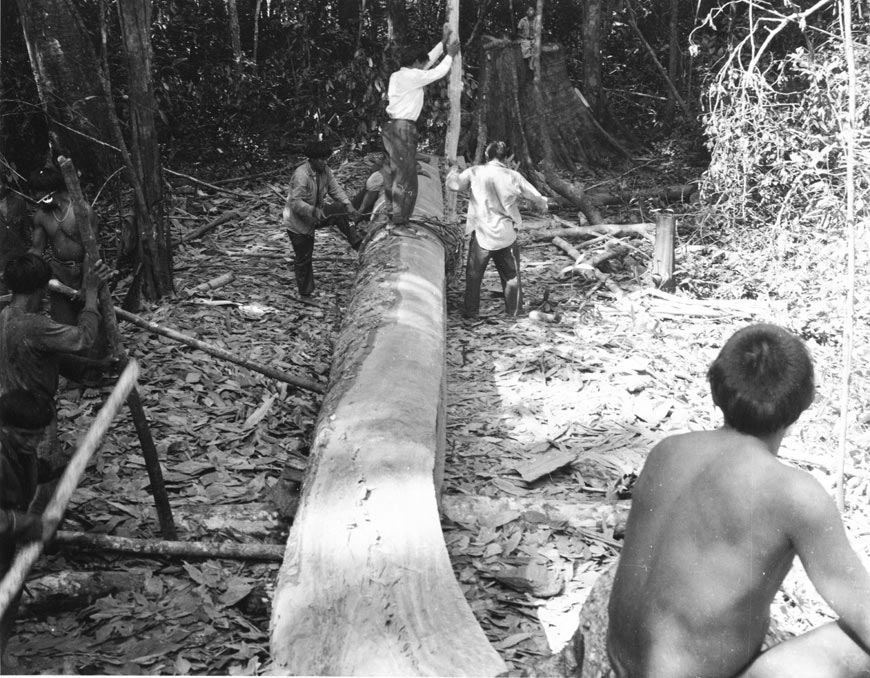

The Ye'kwana always travel by river but in some instances they must use a land trail to avoid waterfalls and rapids. Here they are pushing their very heavy dugout curiara through a trail lined with pieces of logs so their large canoe will slide more easily.

Environment

The development of navigation skills allowed the Ye’kuana to settle a wide river territory. As a result, they inhabit the banks and surrounding areas of a number of the Orinoco's tributaries, covering approximately 30,000 square kilometers of the present-day Venezuelan states of Amazonas and Bolivar.

Ritual and Tradition

For the Ye’kuana, material culture is tightly bound to the realm of the sacred. Thus, the objects they use for navigation, hunting and fishing, farming, and ritual can be seen as an expression of their spiritual and social lives.

For example, the construction of the communal home, known as the atta, has religious significance. In the past, it was a ritual experience that was celebrated with food, drinks and music.

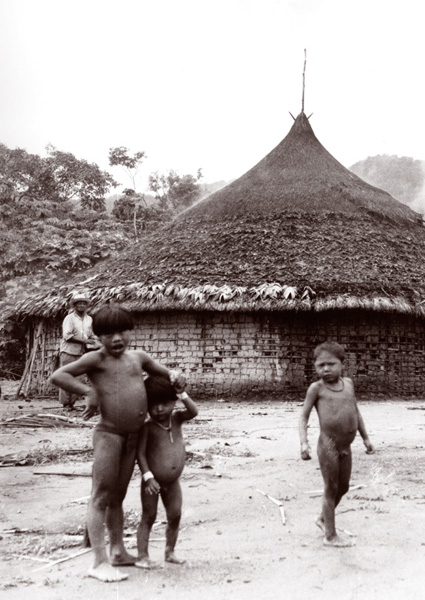

Elegant Ye'kuana churuatas. They can measure up to 30 meters in diameter.

The atta are circular; from afar they appear to be big baskets covered with braided palm leaves.

To build an atta is to symbolically reproduce the great cosmic home, just as the Creator Wanadi did. The atta’s construction is based on the structure of the cosmos. The central pillar is considered the tree of life that unites the earth to the world above and the world below. The circular beams supporting the roof are called "celestial beams," and the girder that supports the beams is always oriented in relation to the Milky Way.

Each atta has a central space with a door that faces the rising sun. This position reflects the belief that each new day is a triumph for the deity of the sun.

The morning ceremony to welcome the dawn – which today only lives in the memories of the very old – was accompanied with dances and the melody of the sacred trumpets.

Although it is apparent in every aspect of their lives, the aesthetic sense of the Ye’kuana is particularly striking in the way they adorn their bodies. In the past, both men and women removed their eyebrows and eyelashes as well as underarm, pubic and facial hair, often with bamboo knives. They also decorated their earlobes with metal earrings and large cylinders of bamboo with colorful feathers.

This eye-catching, ceremonial ornament for Ye'kuana men consists of a whittled piece of wood in the shape of the sacred bat, from which hang the skins of ten or more toucans (Ramphastos vitellinus). The bearer uses it in ceremonial dances, carrying it on his back, while wearing a necklace of peccary teeth (Tayassu pecari).

One important male ceremonial adornment is the ansa, a wooden carving of a sacred bat. It is arrayed with stuffed toucans and worn over the back, along with a necklace of peccary teeth strung on cotton threads.

Other ritual objects include the benches, maracas, and the sonorous walking sticks of the shamans. Once exclusively used to signal shamanic power, today these objects are made for commercial sale.

For the initiation rite that marks a girl’s passage into adolescence, the women weave a guayuco, or loincloth, using cotton threads and red, blue, and white crystal beads called muwaaju.

They also weave hammocks and guanepes, woven bands of fabric used to carry infants, using a rudimentary loom or simple wooden frame.

Fabrication

The Ye’kuana are known for their basket weaving. Guapa baskets, like the atta, are designed from the center toward the edge. The designs, which vary with each maker, convey a complex geometry. Some designs represent the sacred animals that figure prominently in their myths such as anacondas, monkeys, picures, báquiros, and frogs.

The Ye’kuana have traded baskets, among other goods, since the eighteenth century. Today they directly distribute and sell their own products.

Baskets are generally woven by men. However, Ye’kuana women have turned the weaving of the wuwa, a basket for heavy loads that is shaped like an hourglass, into a successful commercial practice.

Other baskets include box-shaped petacas, nasas used to trap fish, and fans to stoke fires or flip cassava bread.

Ye´kuana man weaving a long basket or “Tenke” (sebucán), used to squeeze out the poisonous sap of the bitter yucca, a staple crop.

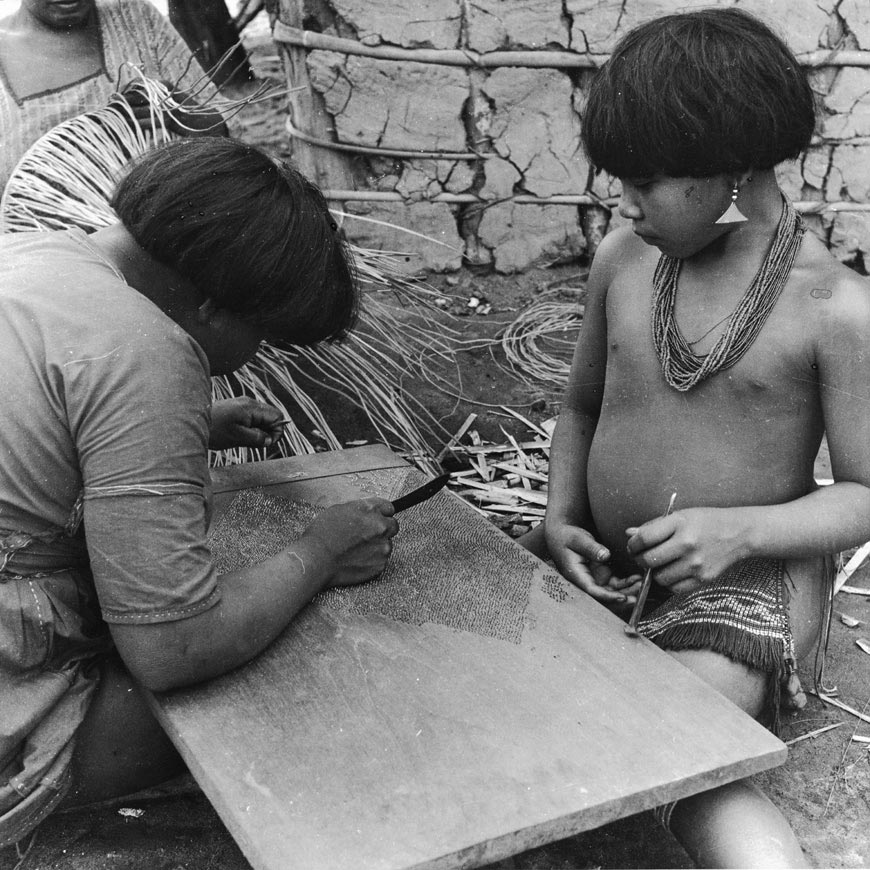

Children learn basket weaving through observation rather than through formal schooling. First, they learn to recognize the raw materials, then how to prepare the dyes. They weave their first baskets as if playing a game but under close adult supervision. Techniques and designs for baskets that require more experience are learned throughout their lives.

Sustenance

The Ye'kuana's diet is quite varied. Besides the mainstay of yucca, the Ye'kuana trap birds like the paují and the toucan, whose feathers are also used as adornments. They hunt a large variety of mammals, and fish using bows and arrows and blowguns. They also use barbasco, a plant whose toxin stuns fish so that they float to the surface of the water. Fruits and vegetables, honey, and insect larvae are gathered from the forest.

In addition to those made for trade, many types of baskets are made for the preparation and consumption of bitter yucca, a staple of the Ye’kuana diet. For example, women carry the yucca from the canucos in catumares. After grating, they put the pulp of the yucca in sebucanes to extract the poisonous liquid. Finally, they sift the flour in the manare.

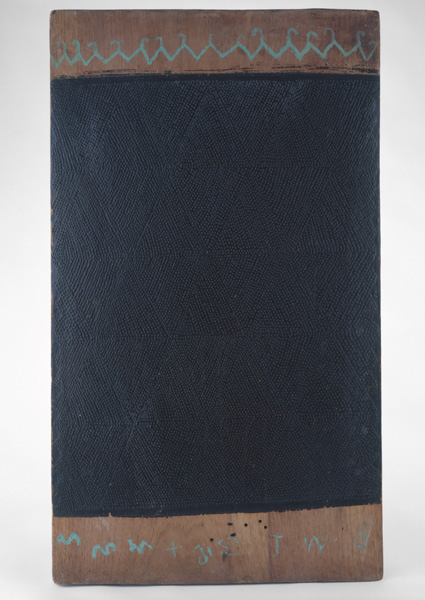

Another object linked to the preparation of bitter yucca is the grater. The traditional method for making a grater is time consuming and labor intensive. Hundreds of small, pointed stone splinters are arranged into a subtle geometric design, then attached to a prepared board with peramán, a black resin. The ends of the board are then painted with red and black drawings.

Work tasks are divided according to gender. Ritual customs and everything that pertains to that which is sacred is assigned to the men. In addition, men hunt, fish, and clear out the conucos. They are also in charge of building curarias, homes, baskets, and ceremonial objects.

Women, responsible for all tasks associated with fertility, play an important economic and symbolic role. Their work often demands intense physical labor as the women maintain the productivity of the conucos, sowing the land as well as carrying the large, heavy baskets filled with the products of the harvest.

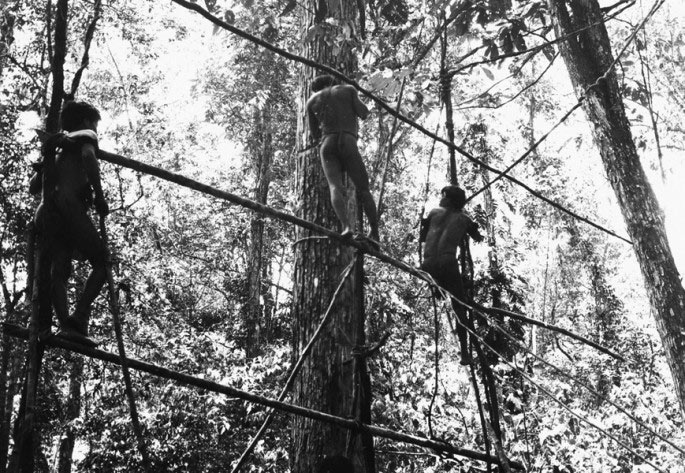

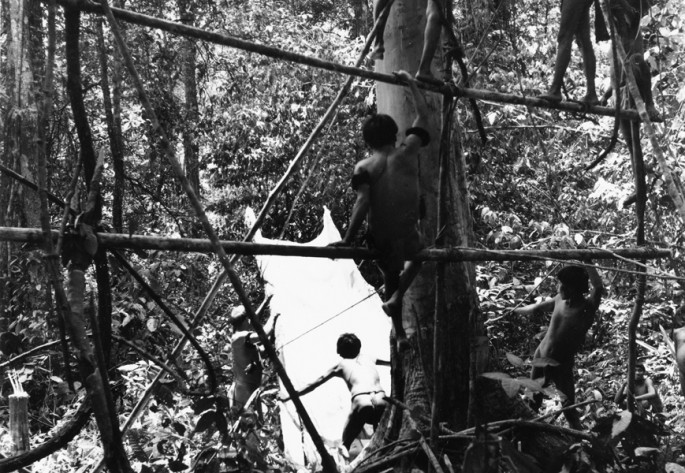

Dependent on the river systems they so ably navigate, the building of the curiara is central to the Ye’kuana identity and way of life. A curiara is made from the trunk of one gigantic tree, which is cut down then hollowed out into the shape of an oval.

The outside is sanded and polished with metal axes and machetes until the shell is completely smooth and even. The interior of the curiara is then widened with fire. In a slow and painstaking process, small portions are burned. As the fire opens up the spaces, crosspieces are inserted to prevent shrinkage.

Afterwards, boards are positioned inside to be used as seats, and the curiara is ready to launch in the river. The paddles are heart-shaped, sculpted out of hard wood and then painted with red and black designs.

When the curarias have outlived their usefulness as boats, they are used to store the pulp of freshly shredded yucca, to wash clothes, or to store the fermented beverages consumed at parties and rituals. Over time, the curiara returns to nature, and completes the cycle of life.