History

Little is known even now about the history of this group, in part because of their geographic seclusion. Protected by dense forest and rivers which are difficult to navigate, the Hotï have been insulated from the invasion and exploitation that affected the region during the first half of the twentieth century.

The word closest in meaning to Hotï is "man." Although the origin of the Hotï language is unknown, some believe it is related to the languages of the De'aruwa and Sáliva. Others find similarities in vocalization and nasalization to the Yanomami.

Environment

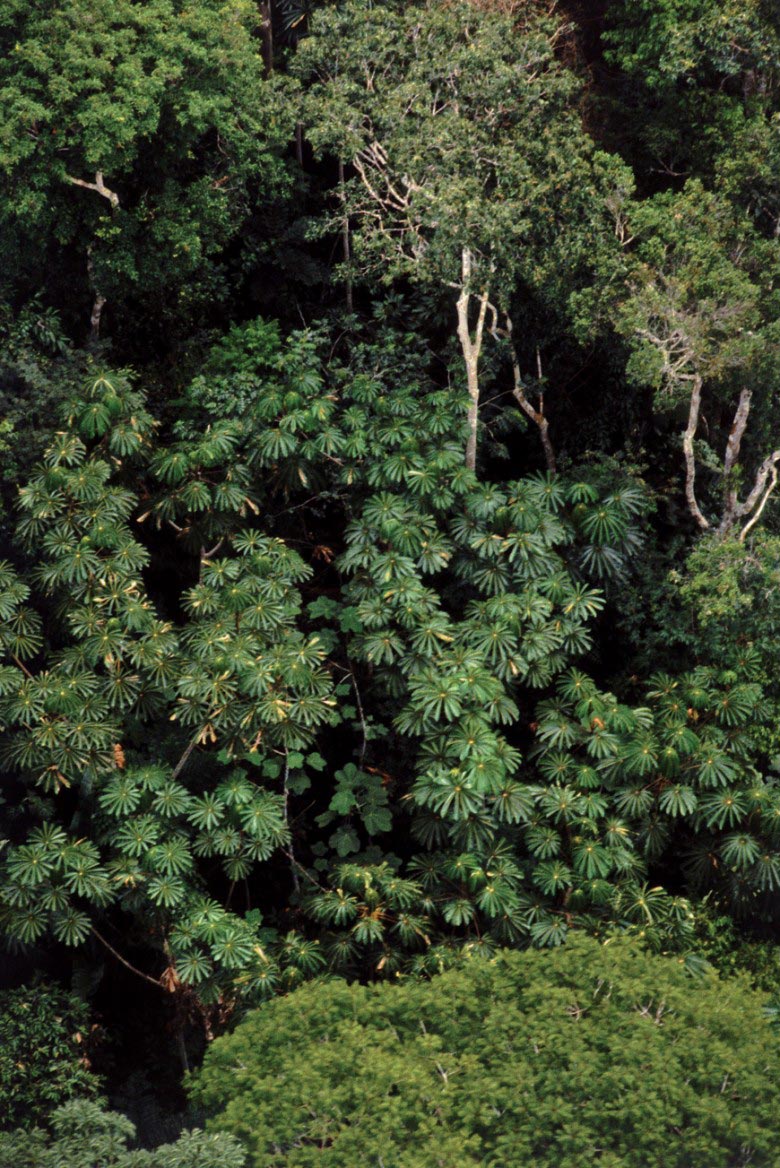

The Hotï live within the middle-superior basin of the Orinoco, northeast of the Escudo Guayanés. They occupy jungle regions bounded by the Kaima River in the north, the Maigualida mountain range in the east, the Asita River and Majagua channel to the south, and the Parucito and Cuchivero rivers to the west.

One to four related family groups live in temporary settlements. They move often, particularly during the dry season. A house may include one family or be shared communally, in which case, each family has its own area for sleeping, cooking, and personal belongings.

The Hotï have domesticated several types of animals as pets: monkeys, agouti, chiguire, turkeys, parrots, toucans, owls, pheasants, cranes, and woodpeckers among them.

Sustenance

Plaintains are the most important plant food of the Hotï, who plant small gardens in addition to gathering food from the forest. During the dry season, the Hotï hunt tapir and peccaries as well as smaller game. The game is shared, with the head, breast and front legs going to the hunter, and the remainder divided among relatives.

This cerbatana is extremely long, which multiplies its precision and potency. This was the first Hotï object that González Niño collected, since this culture was unknown until the early 1970s.

To hunt small animals, the Hotï employ a variety of techniques. They make lures; set traps, or build blinds out of vegetation from which they can kill their prey with blowguns and curare-treated darts.

Fabrication

In the northern area of their territory, near the Kaima and Cuchivero rivers, the Hotï have ties with their neighbors, the E’ñepa. The two ethnic groups produce similar housing, cotton hammocks, cooking utensils, musical instruments, basketry, clothing, and body decorations.

This piece from the Iguana estuary, a Ventuary River tributary, is extremely unusual since the Höti, like the Yanomami, rarely use musical instruments.

Unlike the E’ñepa and other ethnic groups, the Hotï do not use bird feathers as adornment. They do, however, make necklaces from seeds, bird beaks and bones, and danta hooves. They also pierce their ears with bamboo shoots, báquiro teeth, or slivers of monkey bone, and use vegetable dyes for body painting

Through E’ñepa influence, the Hotï have begun to wear guayucos, or loincloths, which they also fasten with belts of human hair. Usually woven in cotton, men wear a rectangular strip tied around the waist; women just cover their pubic area. In addition to wearing loincloths, adults tie strips of cloth or human hair around their wrists, legs, and ankles. Boys tie cotton string around their bodies.

The Hotï live in an isolated area that is removed from cultural exchange. Therefore, the cooking vessel has a primitive design and thickness. The amount of soot is evidence of its extensive use.

Hotï ceramic artistry also reveals an affinity to that of the E’ñepa. Vessels are formed from rings of clay that are smoothed together with a piece of a gourd. Once dried, they are baked over an open fire. Gourds also are used as containers to store and serve food and water.