History

Like other ethnic groups of the Río Negro region, the Baniwa suffered greatly from exploitation by the rubber industry during the early 20th century. Their numbers were diminished and their culture transformed.

Despite acculturation and assimilation, the Baniwa have retained some of their ancient mythology. Their Creator Nápiruli (Iñápirrikúli) is a deity also honored by other Arawak groups of Southern Venezuela and Colombia. The Baniwa belief system has much in common with the Tsase, Warekena, Wakuénai, and Baré peoples.

The Baniwa, also known as the Curripaco, speak a language belonging to the Arawak linguistic family. Like their belief system, their language is closely related to that of the Baré, Tsase, Warekena, and the Wakuénai. It is spoken by approximately two thousand people scattered throughout Venezuela, Colombia, and Brazil.

Environment

The Baniwa live on riverbank villages and in some urban centers.

Today the remaining Baniwa live in Maroa, capital of the department of Casiquiare in the Venezuelan state of Amazonas, and in Colombia, near the Caño Aquio and the Isana River. The region’s history of violence also spurred migration toward San Fernando de Atabapo, San Carlos de Río Negro, Santa Rosa, Puerto Ayacucho and the Xié River in Brazil.

The progressive abandonment of their ancestral ways of life has made the Baniwa increasingly dependent on industrial products, including food. The Baniwa still do seasonal hunting and gathering, but as their children attend criollo schools, it is difficult to coordinate collective activities with the school calendar.

Fabrication

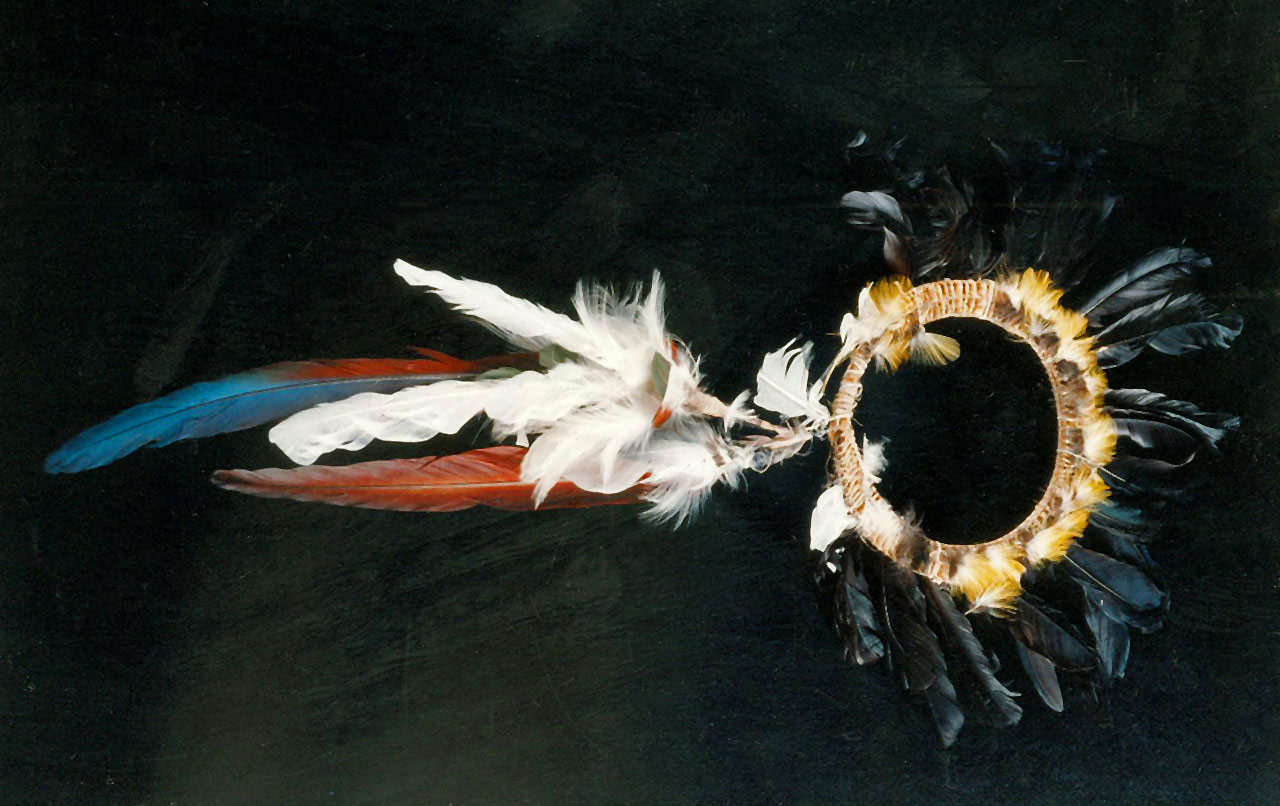

As all indigenous peoples of the Amazonas region, the Baniwa fabricated the things they needed for their rituals and daily life from the natural materials around them.

Ritual and Tradition

Among the traditions the Baniwa still practice are music-making, dance, and the generational transferrence of their legends and beliefs.