History

One of the first reported encounters with the Híwi, in the 16th century, described them as hostile nomads living in the llanos (savannahs) and the region of the River Meta. Although some Híwi managed to elude European colonizers by moving into rough terrain, others were enslaved or exterminated.

The Híwi call themselves the “people of the savannah” for the vast flatlands they inhabit between the Meta and Vichada rivers in Columbia. In Venezuela, the Híwi live in the states of Apure, Guarico, Bolivar, and Amazonas. They are also known as Guahibo.

The design of Hiwi arrowheads are specialized depending on prey. The inversely serrated arrowheads are used for fishing.

Seventeenth and eighteenth century historians described the Híwi as nomadic hunter-gatherers. Their long history of violent conflict and the incremental loss of their traditional lands, extending well into the twentieth century, has meant dramatic changes in their way of life.

Sustenance

Although some Hiwi still maintain a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, within the past 100 years, more have taken up slash-and-burn farming, growing manioc, sweet potatoes, yams, peppers, plaintains, sugar cane, tobacco, barbasco, and medicinal plants; the care of livestock on the large estates of the savannahs; commercial trading of traditional crafts; and day labor to sustain themselves.

Many of the Híwi have become settled farmers or agricultural workers. When those families who farm can leave their crops for a while, they sometimes retreat to a palm grove to relax, living off the fruit of the palms and whatever else they can gather from nature.

Ritual and Tradition

The Híwi believe that all people and animals have two souls. The invisible Yethi leaves the body during sleep to appear in others' dreams. Húmpe only leaves at death, when it travels to the celestial dwelling place of Kuwai, the creator for the Híwi. The shaman's húmpe goes to live with a great snake in the bottom of a river.

Today, when the Híwi visit criollo towns, they wear European-style clothing rather than the traditional loincloths made of cloth or of a vegetable bark called marima. Traditional clothing also includes body ornamentation. The Híwi make necklaces of glass beads as well as shamanic amulet necklaces for ceremonial use.

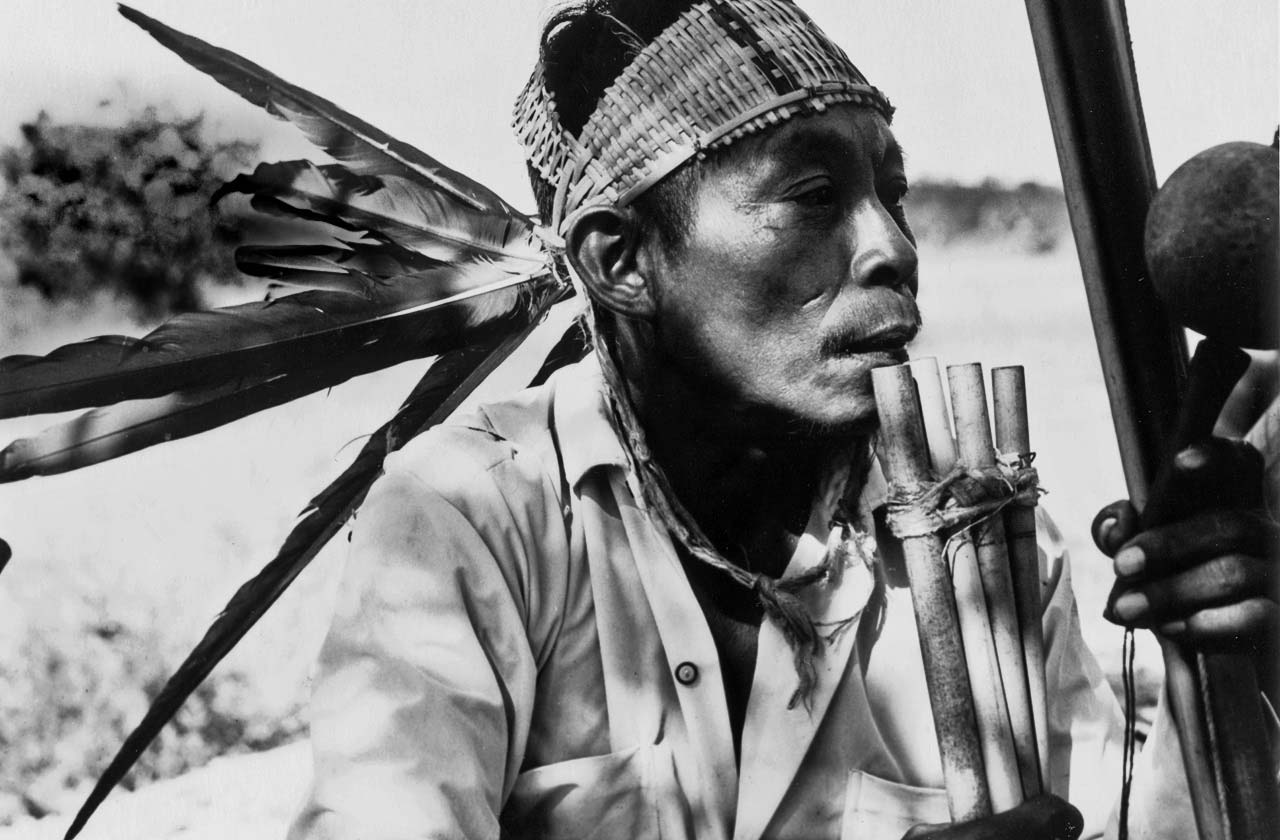

The shaman is the Híwi's highest spirtiual authority, able to work white and black magic. His maraca, traditionally used for healing, is made from a dried gourd painted with geometric patterns, and often decorated with a tuft of curassow feathers. Special maracas have crystals inside rather than seeds; the sound the shaken crystals make brings the power of ancestor shamans to life.

The Híwi make wind and percussion instruments to use in festivities and ceremonial rituals. Some examples are large deer bone flutes with three holes; and pan flutes, made with five or six tubes of caña amarga, that often are played with another musical instrument made from the skull and antlers of the deer.

Fabrication

The Hiwi believe that the world was created by supernatural beings, with a number of "culture-bearers" who taught the Híwi how to make the things they need: among them, Iwanai taught the Híwi how to build huts; Matsúáludani, who showed them how to use bows and arrows; and Madúa, who invented language and taught the Híwi how to build canoes.

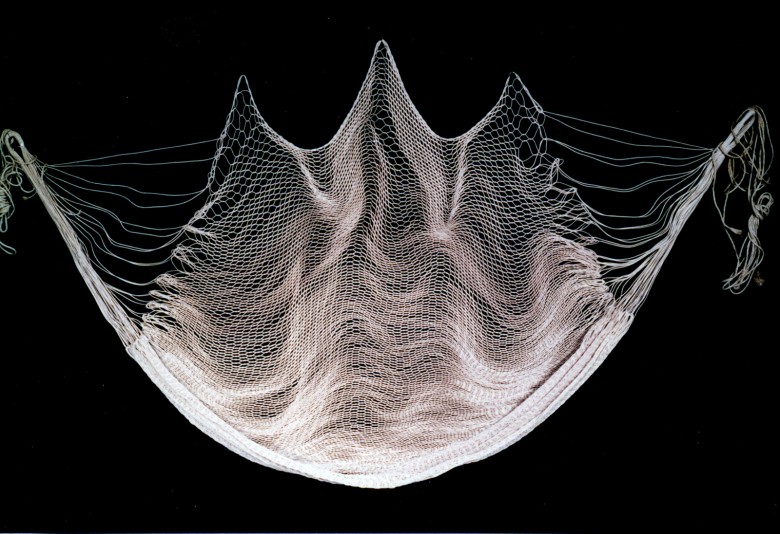

Textiles are an important part of their material culture. The Híwi weave high-quality chinchorros (hammocks) with moriche or cumare fibers, using looms with double horizontal weaves.

Historically, basketry has been a male occupation among the Híwi, and the baskets they weave for transporting and storing foodstuffs are decorated with red and black geometric designs. Recently, women have begun to make baskets for commercial sale.

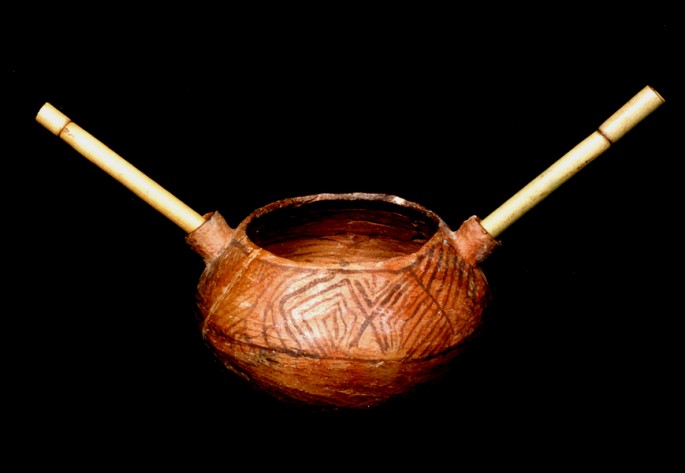

Some Híwi still make pottery, although far fewer do since the introduction of aluminum pots and plastic containers. Traditionally an activity of the dry season, vessels are made by rolling rings of clay over a base. After they dry, they are burned over an open fire and then decorated with vegetable dyes such as cumare and caruto.

A consequence of the introduction of aluminum and plastic vessels, pottery has lately decreased, including commercial ones that were sold to criollos, such as pitchers with femenine shapes and geometric patterns.