History

Of all of the indigenous groups of the Amazon, the Yanomami are without a doubt one of the most studied and well known.

The name Yanomami means man, people or species. Those who are not Yanomami are “napë,” which roughly translates to “people who are foreign, urban, or dangerous.” This is how the Yanomami refer to everyone who is not Yanomami. Their language is unrelated to any other of the South American language families.

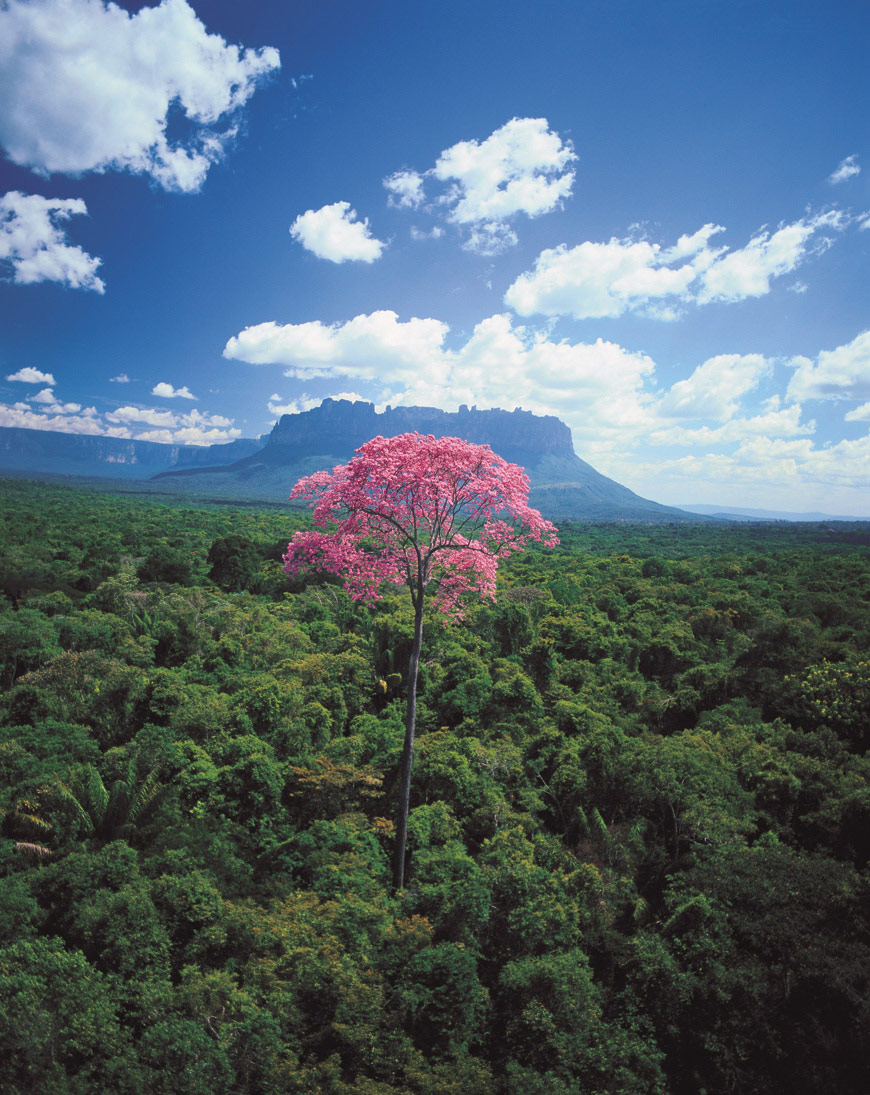

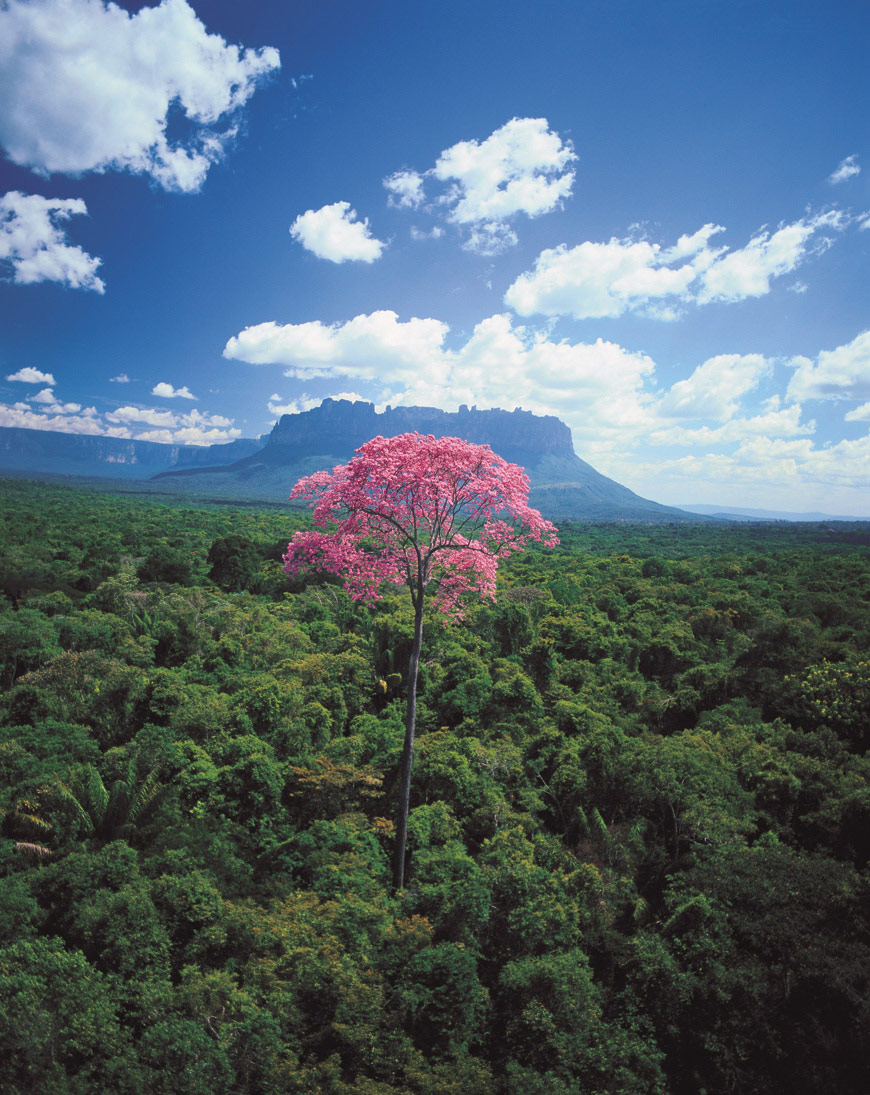

In the foreground, a puy (Eperua purpurea) flowers high above the general tree canopy in February. Beyond is the Auyantepui mountain, site of Angel Falls, the highest waterfall in the world.

The Yanomami are still one of the most populous groups in the northern Amazon lowlands. They inhabited the Parima mountain range and the upper Orinoco as early as 1758.

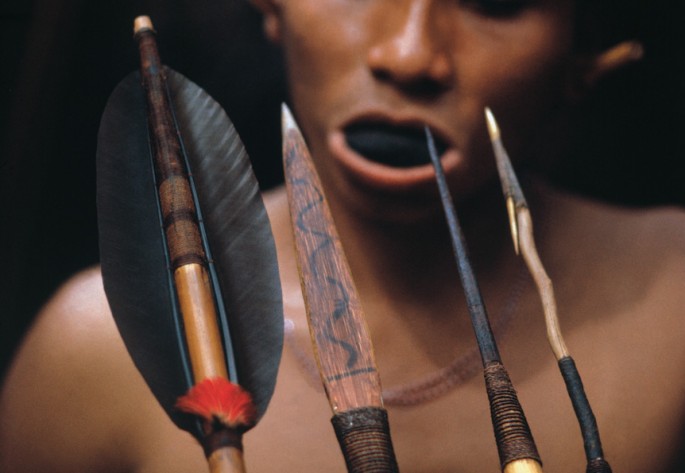

A group of armed Yanomami raiders from the Bisaasa-teri village in the Orinoco river.

At the moment of their earliest contacts with Europeans, the Yanomami had been in the middle of a significant demographic and geographic expansion, exploring new territories along the shores of the Orinoco, Padamo, and Mayaca rivers. In the northern and western zones of their territory, the Yanomami may have clashed with the Ye'kuana, who successfully resisted their advances.

Environment

Most of Yanomami territory, with the exception of some northern savannahs, is covered by tropical rainforest.

Today, the geographic center of the Yanomami in Venezuela is the territory between the Parima mountains and the Orinoco, particularly the basins of the Ocamo, Manaviche, and Mavaca rivers. Groups of Yanamomi also live in the outskirts of Brazil.

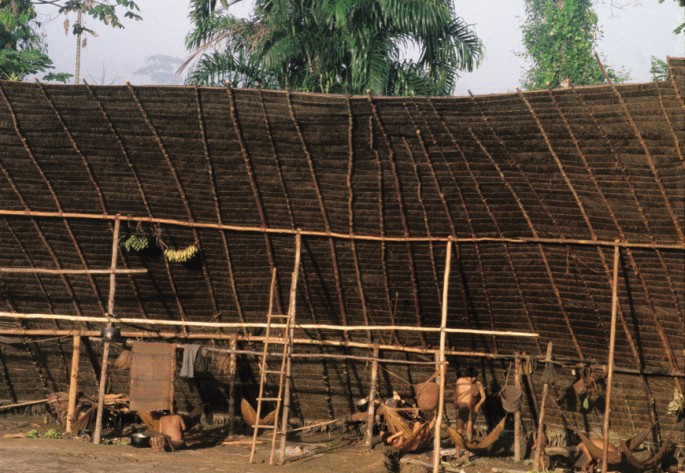

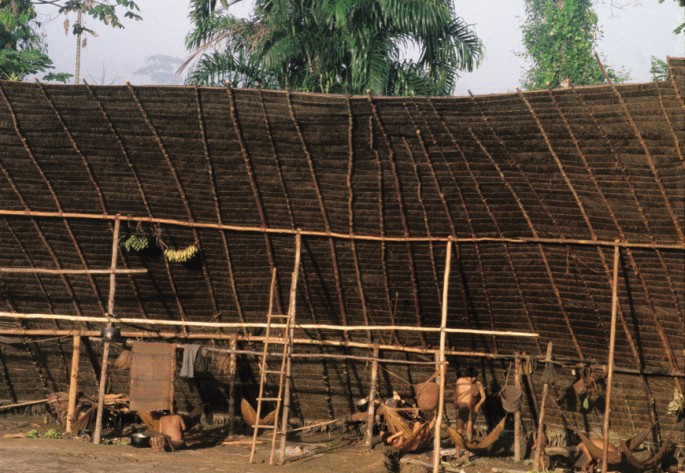

Aerial view of a shabono.

The circular design of shabonos protects against surprise attacks by invaders.

Building a shabono takes several weeks, and both men and women participate in the construction.

Thatching a shabono with the leaves of the Karai-henak, a small palm.

Inside, a series of simple sheds arranged in a circle form a central communal courtyard.

The word "yano" means house, and reflects the central importance of shelter as a distinguishing feature of Yanomami culture. With materials from the forest, the Yanomami build communal houses called shabonos. They are circular, with an outer wall and overlapping lean-to roofs around a central clearing.

Sustenance

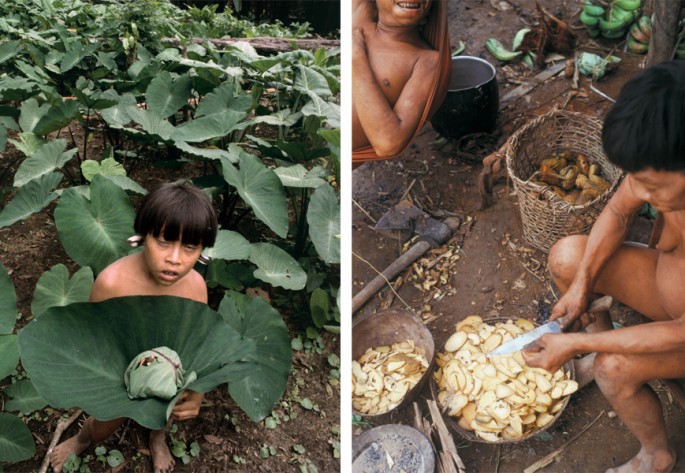

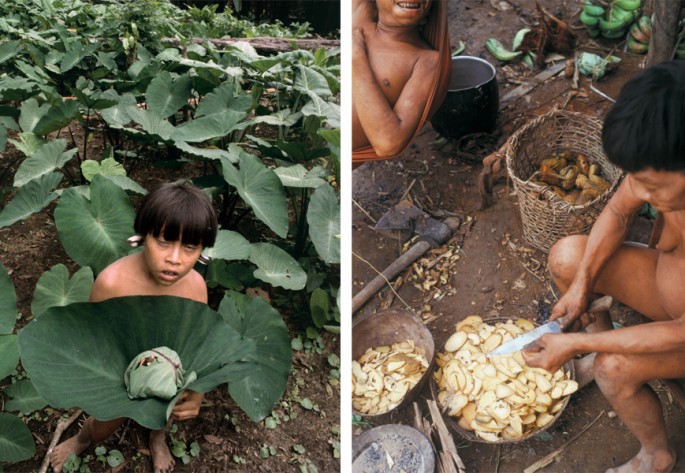

The Yanomami rely on produce from their gardens and food gathered from the forest.

A Yanomami father taking care of his young child in the Konapuma-teri village at the Siapa river, Venezuela.

These hairy, venomous caterpillars are a delicacy and taste like pistachio nuts.

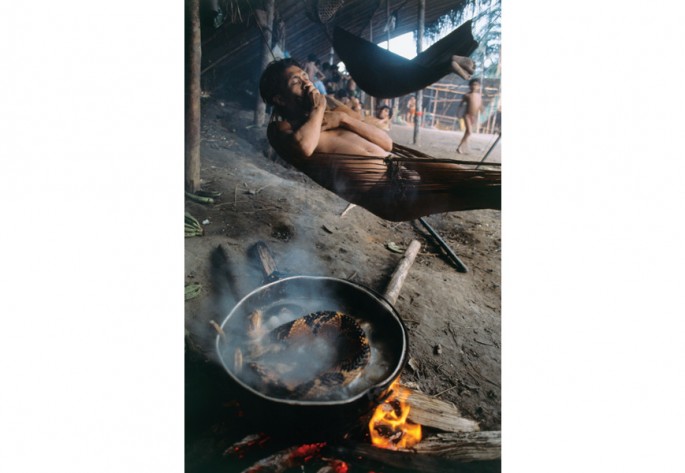

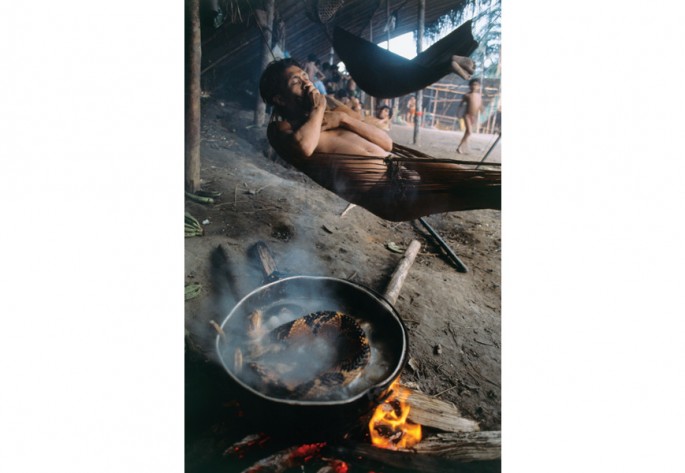

People cook, eat, sleep, and perform rituals within the protection of their shabono homes. Yanomami sleep in hammocks, and children sleep with their mothers until they are four. Each family has a central hearth for cooking, around which they suspend the hammocks. Yanomami eat a wide variety of foods, from snakes, pigs, monkeys, deer, and jaguars to insects, fish, plantain, sweet potato, and palm fruits.

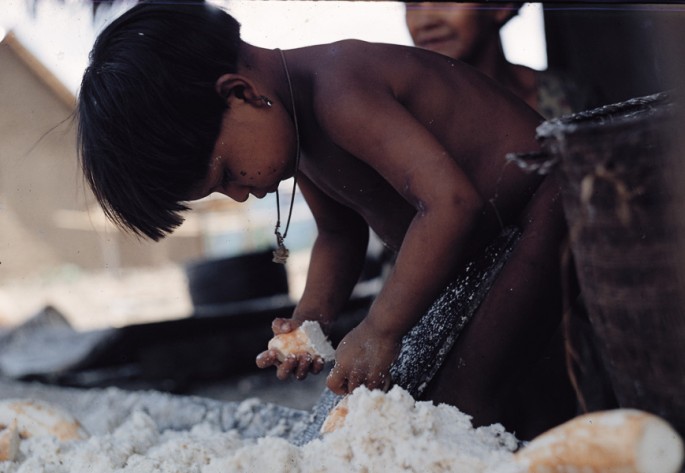

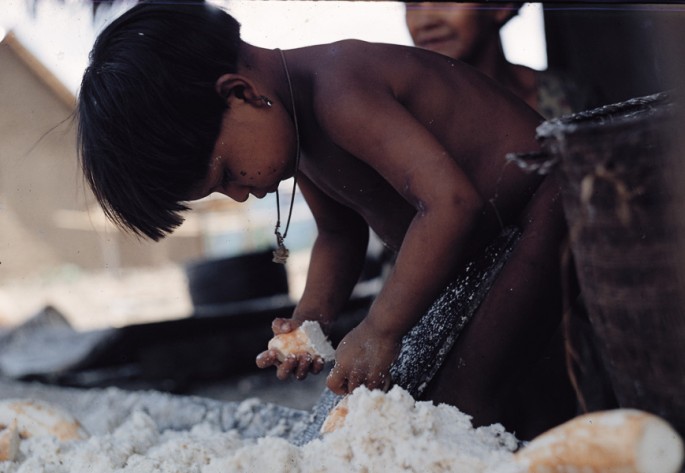

A boy grates bitter manioc.

Families hang their bananas, tobacco and other necessities from the roof of the shabono. Men and women both participate in gathering food from the forest.

The Yanomami communities cultivate simple conuco gardens near their shabonos where they grow food crops, like plantains, sweet bananas, and tropical tubers; and cotton, tobacco, and plants used for rituals and as dyes. Men clear and burn the land in preparation for the garden, and both men and women plant and harvest crops.

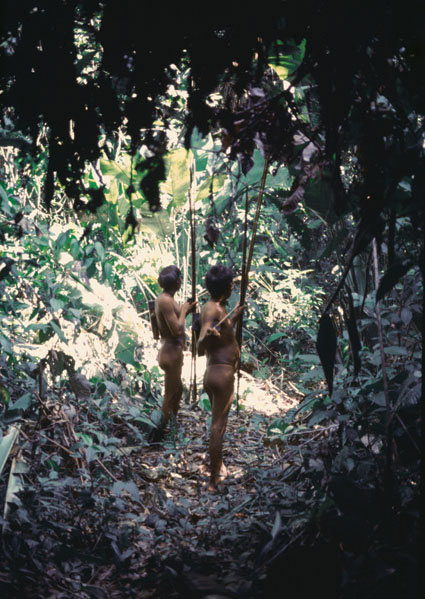

Although agriculture is important to the Yanomami, hunting and fishing are also significant sources of food. The Yanomami distinguish between two types of hunting. One is known as ramï, which provides them with meat for everyday use, and the other is heniyomou, which is performed collectively by all the men of a community for celebrations and special guests.

Heniyomou, a hunt that lasts for several days, is practiced for special feasts. Almost all of the men of the community participate in the heniyomou, while the women and girls remain in the village to perform the ritual hëri, in which they sing and dance to placate the game and entice it to surrender to the hunters.

Almost every day, men will set out either alone or in small groups to hunt. They carry with them bows made of palmwood, and arrows with light, flexible shafts.

Women and children also do some of the hunting, going after smaller animals, fish, and crawfish.

Ritual and Tradition

The Yanomami structure their society with rituals and traditions that guide every aspect of their lives.

For the Yanomami, the collective ingestion of the deceased's ashes is an important ritual. The charred bones, eaten in a plantain soup, are ground in a funerary mortar carved from a tree trunk with fire and axe. Patterns painted on the mortar reflect the deceased’s age, sex, and rank: black dots for adults and old men; red annatto for old women; and wavy lines for younger people of both sexes.

One of the occasions that requires the type of hunting known as heniyomou is the funeral of a member of the group. When a Yanomami dies, the entire community weeps violently. Very soon after the death, a funeral pyre is erected in the shabono to burn the body. In the ritual known as reahu, the ashes of the dead are ground in a mortar and ingested by the community.

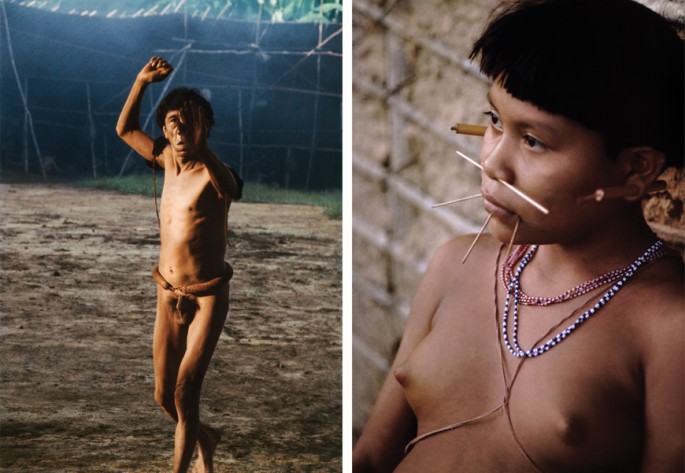

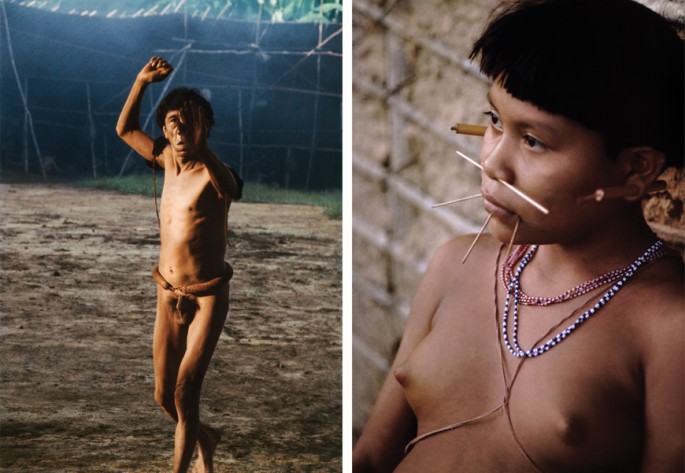

Yanomami girl with tobacco.

Yanomami frequently consume yopo, a hallucinogen, during ritual ceremonies. From around the age of seven, Yanomami habitually tuck wads of tobacco between their lower teeth and lip. Stimulants allow the Yanomami to get in touch with the world of the supernatural, to cure illnesses, and pass on their collective memory.

Each village has at least one shaman, who is the spiritual leader and healer. At some stage in their lives, almost all men undergo the initiation rite to become a shaman. The initiation period takes months, or even years. Under the influence of the drug yopo, the novice submits to the instructions of the teacher.

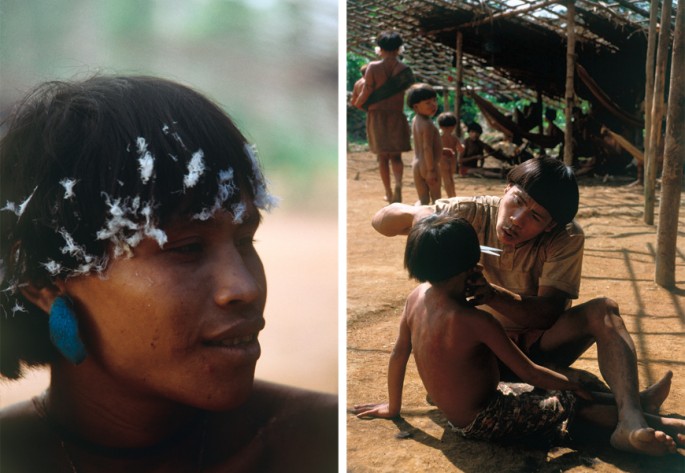

In mourning, a Yanomami woman wears black paint on her cheeks for a year before she can use red again. When men go to war, they wear black body paint to symbolize night and death. For some festivals, the Yanomami apply white clay over their bodies. Body painting with a variety of dyes is common; in addition to black and white, they generally use anoto for red, and for purple, they combine the onoto with a resin called caraña.

A Yanomami boy with ear rings made from toucan feathers.

A group of Yanomami women.

The face paint of this indigenous man from the Erebato river represents a fierce tiger (Jaguar).

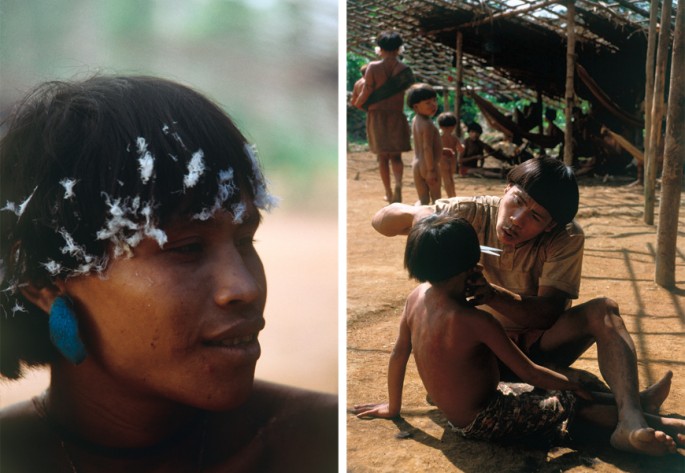

Left, a visiting Yanomami warrior wears the white feathers that show his peaceful intentions, and right, a man cuts a child's hair.

The Yanomami decorate their bodies with colors, patterns, and materials that vary according to the occasion, but traditionally wear no clothing. Men bind their foreskin with a cotton string tied around the waist in order to keep their penis upright and against the stomach. Women tie string around their upper arms and calves, and use cotton ornaments to decorate their hips and breasts.

Fabrication

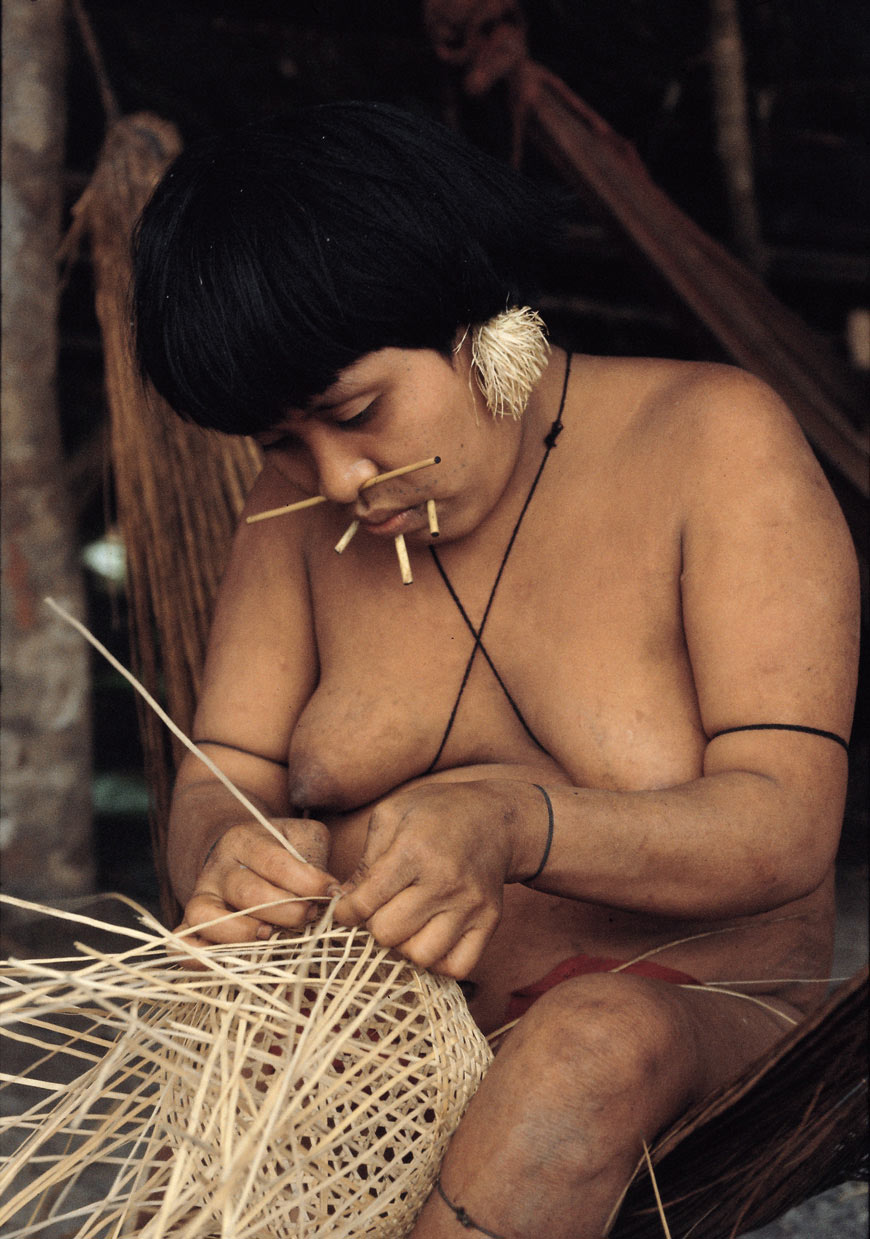

Women make textiles, baskets, and, in the past, pottery; men make hunting and fishing implements.

The Yanomami are usually nude. The few articles they occasionally wear are for adornment, rather than for modesty. This female guayuco, or loincloth, is used by young women in festivities.

In addition to the guayuco, Yanomami textiles include the chinchorro or hammock that Yanomami women weave on rustic frames of wood nailed into the ground. During trips into the jungle, the Yanomami use mamure fiber to weave provisional hammocks, marakami-toku, which are often discarded after the trip.

Yanomami women spin cotton (shináni), using spindles made of wood or a round seed.

This cotton fiber is used to make hammocks and personal ornaments.

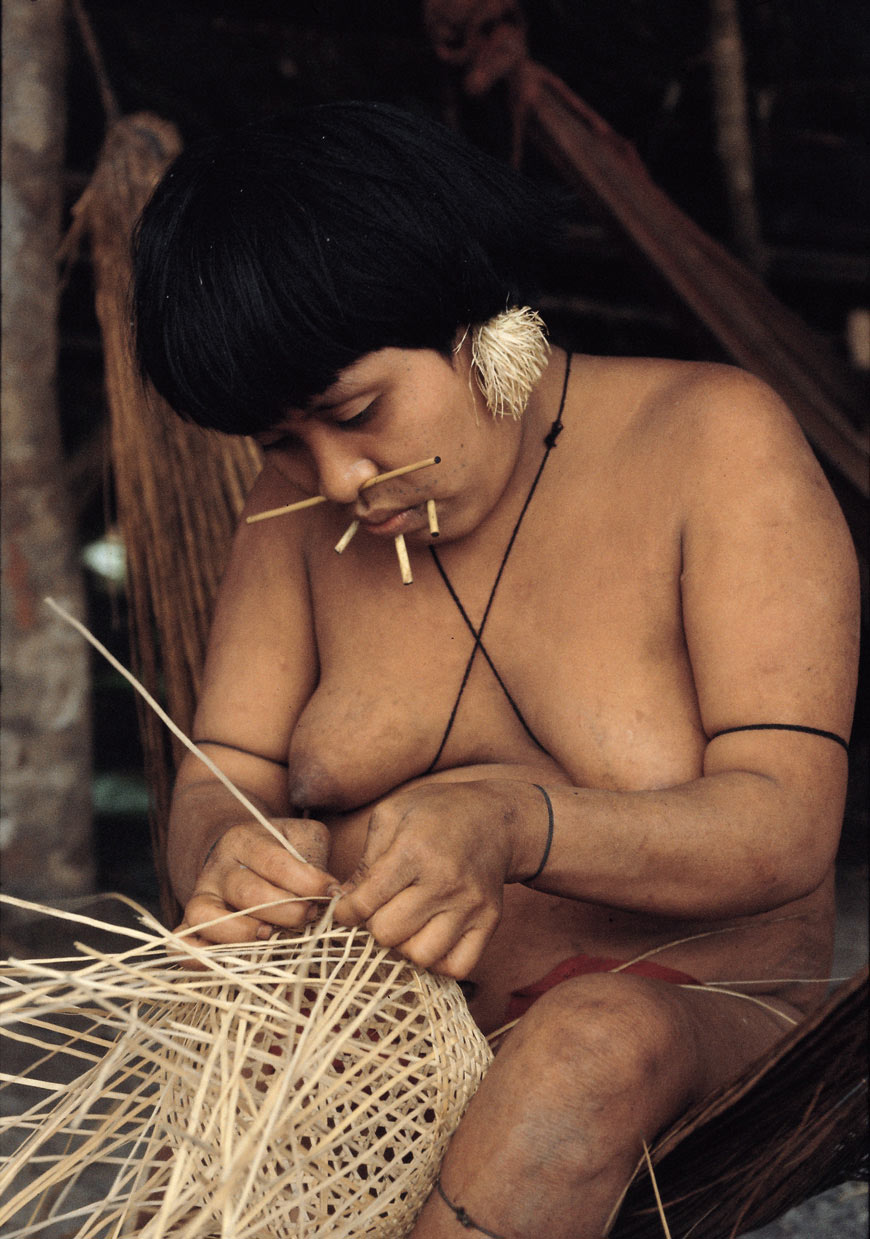

A Yanomami woman from the village of Konapuma-teri at the Siapa river weaves a basket.

Women use mamure fiber in basketry as well. They make guataras, guapas, and manares. They use different shapes and techniques according to the function of the basket.

The guatura is a Yanomami basket used for carrying objects, made with dense braiding and ribbons of marima fibers for hauling. Decoration consists of simple and abstract patterns that sometimes represent sacred animals. Yanomami basketmaking is done by women, who use mamure to weave.

The guatara, a basket most often used for carrying loads, is woven in a dense braid.

The "hapoka" was the traditional pot produced by the Yanomami. Hand modeled from white clay, it was dried in the shade and later fired. Its conical shape facilitated its use in stone ovens. When its short lifespan was over, hapokas were used to prepare yopo or other cooking ingredients. Today, they are increasingly rare, since they have been mostly replaced by aluminum pots.

In the past, pottery was an important artisan craft in Yanomami culture, but today it has almost completely disappeared. Few communities still make the typical hapoka, a plain bell-shaped pot made with white clay. Since metal pots became available, the Yanomami have discontinued their tradition of pottery.

On the left, a Yanomami warrior shows how he moistens the fibers from the bark of the tree Cecropia sciadophylla to make the bowstring. On the right, the figure-eight knot made to hold the bowstring in place.

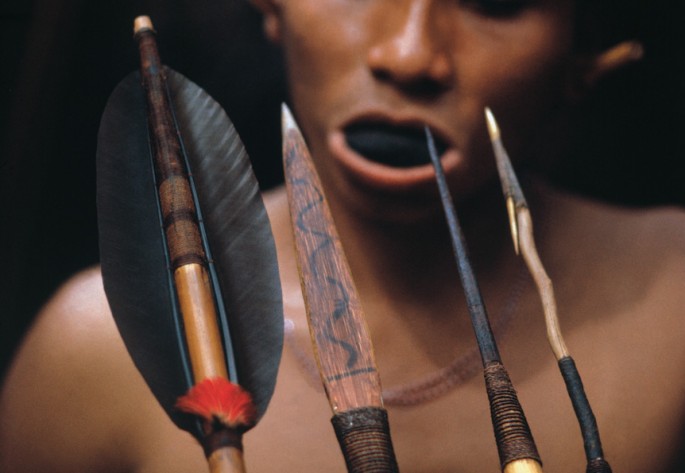

Yanomami man from the village of Bisaasa-teri, in the Upper Orinoco river, with a variety of arrows.

The Yanomami use a very strong palm wood they call "joko" (Jessenis bataua) to make their bows.

The feather and the notched end of the arrow are attached with shinani, a thread made of cotton or the fiber of a bromeliad leaf.

The nock end of the arrow, where it is notched.

The Yanomami have kept the tradition of making bows and arrows alive, although firearms have been introduced, and acculturation has changed many other aspects of their lives, as well.