History

The E’ñepa were first described to the outside world in the mid-nineteenth century, in the travel journals of Augustín Codazzo, who encountered them in 1841.

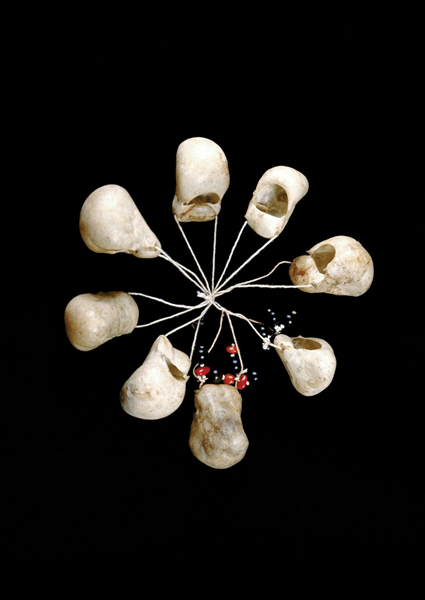

The teeth used in this necklace come from small monkeys which are part of a normal jungle diet.

Although known most commonly as the Panare, these original inhabitants of the Alto Cuchivero region call themselves E’ñepa, meaning "indigenous people." Their language, which has no word for "chief", belongs to the Caribbean linguistic family. They govern themselves collectively, and because of their deep respect for community rule, they have few conflicts.

Environment

It seems that the original ethnic group split into two, with one branch establishing itself in the mountains west of El Tigre, and the other, in the mountains separating the Guaniamo from the plains of the Orinoco.

The Orinoco River is widest when it crosses the savannah regions in Venezuela and Colombia.

The E’ñepa now live at the edge of the middle Orinoco region in the Cedeño district of the state of Bolívar. E’ñepa populations also cluster in the south, near the border of the state of Amazonas. Their territory extends across an almost treeless strip of savannah to swampy palm groves lining riverbanks.

Sustenance

Everyday life for the E’ñepa revolves around farming and hunting, with a sexual division of labor. Men hunt, fish, and clear land for cultivation, and women sow and harvest crops, cut firewood, cook, and raise children.

The cerbatana (blowpipe) consists of two wooden tubes, one inside the other. The interior tube, or kurata, is bamboo or reed, and the exterior tube is made from palmwood, with a wooden mouthpiece to blow the dart. The darts are whittled bamboo, with points usually poisoned with curare. The blowpipe’s silence and potency make it ideal for small game.

The E’ñepa harvest crops, particularly the bitter yucca. Hunting and fishing are also fundamental to their economy. They use blowguns to hunt birds and smaller game. Until recently, they used spears to hunt large animals, like danta and deer; now they hunt with guns.

Bactris gasipae,known in Venezuela as the pijiguao palm, is a major source of food and has been cultivated by the indigenous people for 4000 years.

They fish with barbasco, a toxin that stuns fish, as well as nylon fishing lines and hooks they buy from the criollos. They gather honey and palm fruit like moriche and pijiguao, as well as some varieties of ants and edible worms.

Ritual and Tradition

The shaman of the E’ñepa, the I'yan, is a healer and performs the necessary rituals to observe rites of passage and to protect his people. Many of the motifs found in the stamps the E’ñepa use to decorate their bodies and in the baskets they weave have magical significance.

The E’ñepa express their highly refined aesthetic through body painting, which they practice throughout their lives. Using wooden stamps in various sizes, shapes, and designs, parents paint the hands and feet of their children.

This rattle is made from red-howler monkeys' throats (Alouatta), a howler monkey common in Venezuela. The male howler monkeys' throats are developed to emit a powerful grunt, and is used by the E'ñepa as an amulet for children that are learning to speak.

Red-howler monkey (Alouatta).

Young people decorate themselves with bands of woven cotton. In contrast to other ethnic groups within the region who prefer to wear European-style clothing when visiting criollo towns, the E’ñepa will just as readily wear traditional garb.

Young men and women paint their entire bodies with geometric designs. To produce a reddish color, they impregnate the wooden stamps with dye made from anatto and animal fat.

Fabrication

The E’ñepa weave oval hammocks on simple looms, and make loincloths and decorations from cotton. In the 1960s, they learned the Ye'kuana techniques of basketry, and developed new designs that became highly prized and an important source of income.

Annatto, which is used mostly for body decoration, is also a good dye for textiles, obtaining a bright red coloring.

The E’ñepa usually wear guayucos, loincloths made of cotton and dyed red with anatto. The woven fabric is crossed between the legs and tied around the waist with a belt made from human hair. Decorative tassels dangle at each end, hanging over the back of the body.

This piece, probably woven by an apprentice, belongs to the new drawings created by the Panare and inspired by Ye'kuana art. It represents a bat and a path of stars with bands of rain.

Although basket weaving has long been a traditional E’ñepa craft, the practice changed radically when the E’ñepa adopted basket-weaving techniques from the Ye’kuana, allowing them to develop new approaches and designs.

From this period of Ye’kuana influence emerged a brand new and original E’ñepa aesthetic. Although signaling a clear break with tradition, the new E’ñepa designs – highly detailed and artistically innovative – are considered one of their most valued means of artistic expression.